Taking Licks and Rising Again

Losing just about everything created the chance to find what wasn't available.

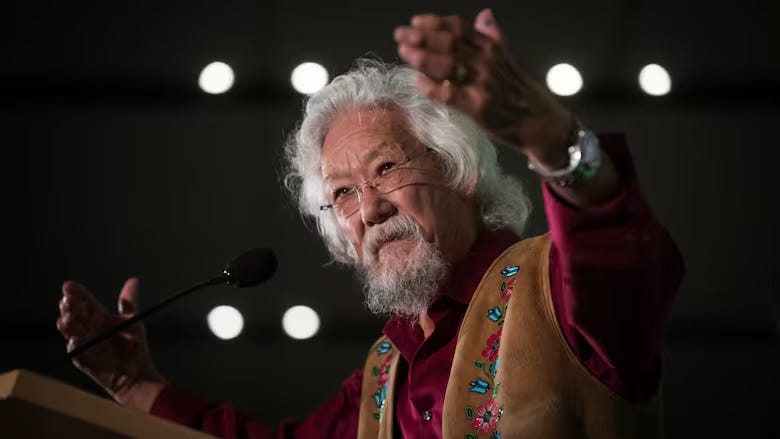

David Suzuki is one of my idols. 21 years ago I read The Sacred Balance and either something shifted in how I understand the world or I discovered a perspective that I innately connected to. The subtitle of the book is ‘Rediscovering Our Place in Nature’ and as a 19 year old I was only discovering my place in nature. Suzuki’s words captivated me. I have no idea now how I came to find, open and read The Sacred Balance, but all these years later it was a moment I didn’t realise would change the trajectory of my life.

I’ve read all of his stuff since, I saw him speak at the Sydney Opera House and I’ve watched many of his various talks online. So when I saw headlines that he’d “given up”, I was surprised but not shocked. “It’s too late… For me, what we’ve got to do now is hunker down.” Is he wrong? The Mauna Loa Observatory recorded a monthly average atmospheric carbon dioxide reading for June of 429.61 parts per million (ppm). The 2024 June average reading was 426.91ppm. The best estimates for keeping global average atmospheric temperature below 1.5°C is 430ppm. So this time next year let’s go out on a limb and predict a parts per million reading of 432.54. Bust.

Let’s remember that 1.5°C of warming since pre-industrial temperatures isn’t a political target, it’s the advice of the world’s greatest climate and planetary scientists. “Our assessment provides strong scientific evidence for urgent action to mitigate climate change. We show that even the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to well below 2°C and preferably 1.5°C is not safe as 1.5°C and above risks crossing multiple tipping points.” Tipping points matter. Crossing their threshold is a near-certain portal to irreversible conditions that are incompatible with how we and most non-human life today relies upon.

Let’s criticise Suzuki though.

It’s clear that a loss has occurred. Many of them. Joshi’s criticism lurches to make the point that a study showed actions of the last 35 years have reduced emissions by “several billion tons of [carbon dioxide equivalent] per year compared to a world without mitigation policies’, equivalent to between 4% and 15% of 2020’s total global emissions.” 4-15%. All of my efforts, your efforts and every other person out there seeking climate justice, economic decarbonisation and the utopia of a clean economy has avoided 4-15% of extra emissions. That’s a loss.

Suzuki points to deeper issues beyond the simplicity of arguing over emissions totals with or without different actions. “We have failed to shift the narrative and we are still caught up in the same legal, economic and political systems.” Legal, economic and political systems have strengthened their neoliberal, short termist, capitalist grip over the last five decades. Greenhouse gas emissions increase annually. Planetary boundary after planetary boundary has been crossed. The number of countries slipping into autocratic rule grows. We feel it in our daily lives too. A transport system in NSW that raised fares, acknowledged 20% of services were late and sacked 950 people was just another month as a Sydneysider. Images of elderly people lying on the floors of hospital waiting rooms hit the news this week. A scandal in the nation’s child care system gets papered over with always on CCTV surveillance ideas (forget the privacy concerns) instead of structural reforms recommended to our Great Political Leaders a decade ago. Name the issue, it’s worsened and worsening.

Suzuki is right. We have failed to shift the narrative and we are still caught up in the same legal, economic and political systems. That is loss.

I hate losing. Losing is anathema to my existence. Competition exists at all times. And competition means must win. The Red Mist descends, a white line is crossed, and all bets are off. It is win or it is loss. Global emissions increasing - regardless of whatever projected differences there may be - is a loss. Passing tips points - a loss. Growing housing insecurity - a loss. Rising child poverty - a loss. More evidence of violence towards women - a loss. Inaction on genocide - a loss.

Illusions of grandeur and a determination to express an position on the right side of history permeates the sustainability profession. If only they’d listen to me, then it’d all fall into place. Not that many are listening. Righteousness, pride, delusion and fear block the ability to acknowledge reality.

Losing is awful. It hits ego and ambition, and pierces the armoury of the stories we tell ourselves.

Losing hurts. It makes real insecurities of unworthiness and not enough-ness.

Losing detracts. It takes something away, it removes an idea or a win or a validation or a desired outcome, it alters the future we had previously imagined.

Losing, though, can create new perspectives, if we’re willing to accept reality.

I’ve lost, you have too.

I lost my grandfather when I was four and remember a devastated mother. I lost my grandmother when I was 11 and bawled my eyes out while listening to Chris Isaac and The Cranberries. I lost my cousin at 19 and with it an innocence of existence. Suddenly someone just like me was gone, out of nowhere, at home. At 38 I lost a marriage and with it identity and security and a future I expected. Everyday as a father I lose the boy I raise, replaced the next by a slightly different one, evolving and growing and changing and being different and becoming something new. Grief dances with gratitude. An appreciation of what is but wanting what was too. At times of loss the only panacea seems like the thing lost. A person, a status, a story, a perspective, a place, a time.

In the past couple of weeks we’ve seen two headline legal cases go different ways. The fossil fuel-aligned Australian Government breathed a(nother) sigh of relief when they were victorious in the Pabai Pabai and Anor case that they had no legal duty of care to First Nations People, Country nor Culture. The stunning ruling in the Internal Court of Justice this week lays down a new gauntlet of potential meaningful action. For the Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change, their victory at the ICJ came from loss, and the fear of more of it. A loss. A win.

Change requires the death of something. Removing, not adding. Surrendering, not gripping. Releasing, not holding. Accepting, not resisting.

From loss comes emergence, re-birth, perspective, wisdom, grit, determination, strength, conviction. I know that myself. I find nothing more difficult than not winning. Only by losing have I grown and evolved. Only by losing have I had the chance to be confronted by reality and acknowledge reality over my illusions of grandeur. Only by losing what was most valuable to me have I had the chance to explore what else could be.

See you in the pit - the wins are for taking.

Nourishment, Belonging & Wisdom for The Change Maker

Events have been powering along and many more are planned for the remainder of this Gregorian calendar year.

A couple of weeks ago over 40 people gathered for ‘Listening to The Inner Knock - Making The Jump to What’s Next In Your Sustainability Journey’, a night to hear from, listen to and take lessons from others in our field who are intrapreneurs, transitioning jobs and careers, or making big jumps. The feedback was phenomenal, the night was everything Finding Nature is about and it allowed me to share my story on making Finding Nature for the first time.

We have more coming up, follow on Humanitix and get tickets to support HalfCut and my effort to raise $15,000 to contribute to efforts to Heal Country and Culture, and to enjoy our next supper club getting into all things the law, climate, the environment and the role of the legal system to support safe and healthy futures.

Where the Wild Things Were

Dr Eliza Middleton notices. Life too easily passes us by. Not just the days and weeks and years, but the scents and flowering buds and ever-shifting expressions of each season. Eliza notices.

“Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you got 'til it's gone?

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot”

Joni Mitchell’s lyrics from 1970 still resonate, perhaps more urgently today than when it was first written. What once felt like a catchy protest against urban sprawl now reads like a quiet prophecy. Across the globe, ecosystems are eroding, species are vanishing, and familiar rhythms of daily life are shifting, often without notice. Loss, whether personal or planetary, rarely announces itself. More often, it accumulates slowly, becoming visible only in hindsight. And by the time we truly see what’s gone, the damage is already deep.

I used to walk the same suburban streets every day, past neat gardens and tidy lawns bordered by an ever-thinning line of trees. I didn’t really notice, at first. Trees come and go, I reasoned. One gone here, another there, some removed for the new luxury townhouse, others lost to storms or disease, or slowly strangled by their proximity to pavement. But over time, it hit me…

The treeline was retreating.

That once-thick fringe of green that softened the neighbourhood had hollowed out, leaving behind a sense of exposure, a kind of quiet ache, an echoing emptiness

It made me think about how loss often arrives unnoticed, not with a bang, but with a series of small silences. And not just ecological loss. A friend moving away. A job that once held purpose now drained of meaning. The vibrancy of youth shifting under your feet. And in the larger world, wildness becoming rare, weather turning hostile, species vanishing from places they once belonged to.

So much is being lost, and yet so little of it feels tangible until something finally snaps into awareness. We don’t always see loss as it’s happening. We see it in hindsight, and sometimes that hindsight breaks us open.

The baselines are shifting

There’s a term for this slow-motion forgetting: shifting baseline syndrome. It describes how each generation accepts the degraded state of the environment they grow up with as normal, unaware of how much has already been lost.

One study that captures this elegantly visualised the once-dense herds of North American bison, millions of animals that roamed freely across the Great Plains, so vast in number that early European settlers described the ground as moving beneath their hooves. In the 19th century, it’s estimated there were upwards of 30 to 60 million bison. By the late 1800s, relentless commercial slaughter, westward expansion, and government-sanctioned efforts to undermine Indigenous communities, fewer than 1,000 remained. The study used layered satellite imagery and historical data to show how these herds would have blanketed entire counties at a time, forming migratory waves that shaped entire ecosystems. Today, most bison exist only in managed reserves, fenced in and severed from their ancient, roaming patterns. The scale of that former abundance is almost inconceivable to us now, which is precisely the problem.

This staggering collapse is not unique. Off the coast of Queensland some shark populations have declined by as much as 92% in the past 50 years. These apex predators, once essential to the balance of marine ecosystems, have suffered steep losses from overfishing, habitat destruction, calls for shark culls, and policy failures. Just like the bison, their disappearance has unfolded gradually enough to elude mainstream alarm, yet rapidly enough to upend ecological stability.

Similarly, coral reefs, old-growth forests, and native grasslands have faded, not always with drama, but with a steady disappearance that makes it harder to comprehend what’s been lost. The quieter the vanishing, the harder it becomes to mourn.

We won’t see the diversity our parents saw. In many cases, we won’t even see what we saw as children. Some of the birds I grew up hearing in the mornings, trills that felt eternal, are now on threatened lists. And in all likelihood, they won’t return.

In Australia, the decline has been especially stark. According to The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020, one in six Australian bird species or subspecies is now nationally threatened. BirdLife Australia’s Threatened Bird Index shows that these species have declined by nearly 60% between 1985 and 2020, a trend driven by habitat loss, fragmentation, and climate pressures. The Regent Honeyeater, once common in eastern woodlands, has declined so drastically that young birds often fail to learn their species’ song; there are too few adult males left to teach them. Meanwhile, large areas across our continent, nearly 70%, according to a 2022 WWF analysis, have lost entire bird communities that once defined the landscape.

And this isn’t just something happening in distant wilderness or national parks. It's happening right here, in our cities and suburbs, under our feet, above our rooftops, and in the trees that line our streets. Urban sprawl, reduced green space, and the replacement of native vegetation with concrete and ornamental plants are steadily stripping city environments of the biodiversity they once quietly hosted. The morning chorus many Australians grew up with is fading, replaced by a quiet that creeps in slowly, almost unnoticed, until one day it’s simply gone.

The problem isn’t just the loss itself, but our numbness to it. And when we do finally recognise it, the realisation can be shattering.

The personal within the planetary

Of course, ecological loss isn’t the only kind we live with. People disappear too, gradually, suddenly. So do ways of life, communities, identities. And the feelings are strikingly similar.

I remember when my grandfather began to slip into dementia.

At first it was just forgetting names.

Then whole memories disappeared.

Then I disappeared.

The grief wasn’t in a single moment, it was in the accumulation of tiny vanishings, in watching someone I loved become unrecognisable in pieces, and who I knew was losing me at the same time.

That kind of slow unravelling mirrors the ecological decline I now see everywhere. When you love a place, or a person, or a future you once believed in, and they begin to erode, how do you hold that grief?

I’ve also learnt that grieving doesn’t mean giving up. The presence of grief is proof of care. Of love. What we grieve, we have cherished. And grief, though heavy, is also a guide.

Collective grief, shared recognition

There is something quietly powerful about realising we’re not alone in this. So many people I meet feel something they can’t quite name, disorientation, anxiety, a dull ache. Climate anxiety. Biodiversity grief. The sense that the world is shifting underfoot and no one taught us how to walk through it.

Sometimes that loss becomes vivid, after a wildfire razes a hometown, or floods destroy neighbourhoods, or when we notice that the insects no longer splatter our windshields. But often it’s a more ambient sorrow, hard to articulate.

The truth is: we are all grieving. Some of us are grieving species. Some are grieving futures. Some are grieving safety, stability, and a world that once felt knowable. Others are mourning relationships, jobs, health, meaning. The specifics vary, but the ache connects us.

Naming that grief, and hearing it named by others, can be incredibly healing. It reminds us we are not going mad. We are simply awake.

Living with loss, not past it

It’s tempting to respond to loss with urgency, to leap into action, to fix, to restore. Or, on the other end, to collapse into despair. I’ve done both, and swung wildly between them.

What I’ve come to believe is that the work isn’t to solve grief, or to outrun it. It’s to learn to live with it. To let it sit beside us at the table. To hear what it has to say. To bear witness.

This doesn’t mean being passive. It means being present. It means listening, to our own inner voice, to the land around us, to those who have lived through and survived losses we can barely imagine.

In that stillness, I’ve found clarity. Sometimes, even a kind of joy. Not in the disappearance itself, but in the deepening connection that becomes possible when we stop pretending everything is fine.

A gentle invitation

If you’re reading this and feeling overwhelmed, by climate collapse, by personal grief, by the weight of simply being alive right now, I want you to know you’re not alone.

We are not meant to carry this alone.

We are meant to notice, to mourn, and also to build new kinds of life from the fragments. We are meant to bear witness, not just to the loss, but to the beauty that still remains. To act, yes, but not from panic. From love.

There are still trees. There are still birds. There are still people who care deeply, who plant seeds they may never see grow, who speak the names of species no longer with us as acts of reverence.

Let your grief teach you how to pay attention. Let it guide your attention to what matters. And then let it open your hands, not to grasp, but to give.

I still walk those same streets. The trees are fewer now, but I still look for them. I still listen. I still grieve.

And that grief, strangely, keeps me rooted.

July on the Podcast

The pod continues on. July was something else. Globally recognised experts, many topics covered and the opportunity to share insights from the world’s best.

Listen wherever you pod.

Subscribe, rate and share.

Conflict & Consequence, Compromise & Sacrifice - Hugh White Has a Clear Picture of The Hard New World

On The Hook - Emily M Bender Isn’t Falling for the AI Hype Machine

Making Good Men - Daniel Principe Champions Boys and Challenges Culture

When the Music Stops - Alexander Pui and Preparing For The Worst

Losing to Grow

Dr Josie McLean has examined how and given space for people, groups and cultures to shift and change over time. Her experience is built on time with those seeking, exploring and desiring this. It’s never straight forward and she more than most understand what must be given up so as to gain.

Fear is a natural response when facing the unknown, particularly when it involves losing the familiar or a quality that we value or relationships we hold dear. This fear, rooted deeply in the potential for loss, plays a significant role in how we approach change. Whether it's the climate crisis, a global pandemic, or societal upheavals, the fear is not just about what we might lose but about confronting what we have already lost without realising it.

I've observed that acknowledging this fear is vital. It is akin to a ghost that haunts our decision-making, feeding on our hesitation to let go of what is known, even if clinging to it is actively harmful. This can be expressed in our resistance to adopting more sustainable practices or delaying action against evident ecological degradation. Fear keeps us from facing reality, creating a state of denial we must move beyond.

It is this fear of loss, triggering denial, that works against us as we might attempt to exercise our leadership and ask people to ‘Wake up!” by sharing devastating news or videos of yet another extreme weather catastrophe. We think we will shake people out of their denial. That’s highly unlikely. More likely in fact is that this approach will drive them further into fear and retreat to their existing biases, further entrenching denial.

“Waking people up’ (even if that is possible and some well-known authors such as Meg Wheatly suggest that it’s not); is an act of gentle expansion from where they already are. My experience is that we cannot jar people from one way of thinking to another. Even the experience of a severe weather event seems not to wake many people up – they become traumatised and are unable to move from their existing state. They wait for the ‘return to normal’.

The capability for generating a space for people to ‘awaken’ is hard won. It seems to require compassion, an ability to start where people are and the courage to open the topic further into the unknown realms of high emotions and unpredictable responses.

Connecting with Grief: A Pathway to Acceptance

Alongside fear is grief—a profound reaction to loss that embodies both the personal and collective sorrow over the state of our world. In ecological circles, we see this as a response not only to what has been lost but also to the potential future losses we anticipate. However, grief, if processed and channelled productively, can be a transformative force. I witnessed and experienced this processing of grief for the world I was raised in and the opportunities I believe are already lost to future generations. It took approximately 2-3 years to process originally and the work is never ending. It’s not the same as mourning a lost loved one. That grief passes with time. Mourning for our environment, all the more-than-human elements of our planet; mourning for our ways of life, our civilisation; and maybe even mourning for humanity as a species – all this returns in waves time and again.

Our grief can become despair. But few remain in despair forever. We come out the other side of it, stronger and more resilient than when we entered it.

Grief and despair does not have to paralyse us, despite the warning from some climate scientists who insist we should have hope. That we can’t operate without hope. What seems to happen once through the despair is that we emerge unattached to outcomes. We acknowledge that we actually don’t know what will happen. It’s not looking good and collapse is a distinct reality – but we don’t know specifically what, when or how or even if. Gaia is a mysterious living system that is unpredictable, uncontrollable and unknowable.

In fact, the process can liberate us. Having investigated the abyss, many ask “whose life am I living?” and decide to alter their lives substantially to live life on their terms – gaining a sense of meaning and purpose by helping others to reshape the way we are doing things now and ensuring we remain kind to each other. We can take action, unattached to specific outcomes and hopes. Hope is the other side of the coin that hosts fear. The reliance on hope can be a form of denial.

I am struck by some words of Joanna Macy’s in her book “World as lover, world as self” where discussing ‘despair work’ she says; “Despair work involves nothing more mysterious than telling the truth about what we see and know and feel is happening to our world.”

To understand our emotions and to process them takes time and a community into which to speak. This is the space of personal transformation in the very truest meaning of the word. And if enough people transform themselves and their lives; who knows what may emerge?

Two frameworks to help liberate ourselves

Joanna Macy’s famous Work That Reconnects provides a framework for engaging with this despair and it is usually undertaken in community – not alone. By fully embracing our sorrow, we make space for acceptance, which is crucial to moving forward differently. This process involves four steps: coming from gratitude, honouring our pain for the world, seeing with new eyes, and going forth. This journey from gratitude to action nurtures connection, compassion, adaptation, resilience and renews our commitment to meaningful change.

In 2018, Jem Bendell published his first Deep Adaptation paper. I read it with my heart pounding as the implications began to sink into me. I had just a few months earlier read Meg Wheatley’s first edition of “Who do we choose to be?” and I denied the painful scenario she was painting. Deep Adaptation reached me. Jem later developed a philosophy to confront the possibility of societal collapse, introduced the 4Rs that later became 5Rs: Resilience, Relinquishment, Restoration, Reconciliation and Reclamation. These principles and associated questions may guide us in adapting to the ecological and social upheavals to come.

Resilience: What do we value most that we want to keep, and how?

Building resilience does not just mean hardening against shocks but adapting our ways of life to incorporate the knowledge of impending change. It’s about creating systems that can withstand the unpredictable and emerging stronger from it.

2. Relinquishment: What do we need to let go of so as not to make matters worse?

This involves letting go of certain assets, behaviours, or beliefs that worsen our overall predicament. It’s an invitation to release what no longer serves us, much like the emotional process of grieving a loss.

3. Restoration: What could we bring back to help us as difficult situations unfold?

Focusing on bringing back what is necessary for sustaining life and wellness on Earth. It might include reviving traditional agricultural practices or restoring ecosystems that support biodiversity.

4. Reconciliation: With whom and with what could I make peace with to lessen suffering?

Making peace with what cannot be restored and finding ways to live meaningfully amid these losses. This goes hand in hand with making amends to both people and planet where possible.

5. Reclamation: What can we reclaim about our lives, communities, economies and nature from dominant systems and beliefs?

The focus here is one taking back our lives, liberating ourselves and our communities and reclaiming our connection to our natural environments. It is about doing so with a belief we can reclaim a sense of meaning.

Recognising the Larger Context of Metacrisis

To embrace, feel and accept these emotions effectively, we must first recognise the larger context of the metacrisis—a convergence of interconnected crises threatening global stability. This lens helps us view our challenges not as isolated events but interwoven issues demanding a systemic approach.

Embracing this interconnected perspective can be frightening, but it also opens up possibilities for collective action and shared healing. As we deepen our understanding of the systemic nature of these crises, we become more equipped to employ adaptive strategies that foster long-term resilience and transformation.

A Compassionate Call to Conversation

Acknowledging the role of fear and grief in navigating today's challenges is not about fostering despair but convening spaces in which people can process their emotions and then, only then, set the stage for authentic and very different action. As we confront these emotions, we invite a broader dialogue around personal and societal values, prompting us to align our actions with our deepest beliefs about what is right for humanity and our dearest and only mother Earth. She is known by many different names including Gaia, Pachamama, Prithvi and Papatuanuku. We can work out how to live in ‘right relationship’ again.

Let us hold space for our grief and harness it as a catalyst for transformation with who knows what outcomes. In doing so, we pave the way for a future where our actions are informed by deep connection and commitment, to each other and Earth.

The Luck of the Draw: Generational Loss and the Young’s Vanishing Future

Few in Sydney are working as tirelessly in helping others realise that other and alternative economic models that govern our society not only exist, but are working in other parts of the world. Tom Foster is on a mission to help us all realise that the realities of the present do not need to be perpetuated.

I was born in 1966, placing me at the older end of Generation X. That makes me one of the lucky ones. When I enrolled at university in the mid-1980s, tuition was free. Like Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, a young Boomer, I received a tertiary education at no cost. My brother, just two years younger, wasn’t so lucky. By the time he graduated, HECS had been introduced, saddling him with debt simply because of his birth year.

That difference in timing, mere luck, meant starting our working lives under very different financial circumstances. In contrast, today’s young people face a perfect storm of insecure, casualised work, rising rents, and decades-long HECS repayments [1]. A free university education might now sound radical, but it existed well within living memory. Albanese’s federal government has rightly expanded access to fee-free TAFE places, which have proven wildly popular. But why not extend that same access to university, just as he once received? Or has the ladder been permanently pulled up?

Housing, too, was once within reach. When I entered the workforce in the late ’80s, the median house price in Sydney was around $170,850 [2], while average full-time earnings were about $500 per week [3]. Many of my peers could buy a home on a single professional income and still enjoy a dignified and prosperous life. Fast forward to today: in Sydney, the median house price has climbed to over $1.21 million [4], while average weekly full-time earnings now sit around $1,976 [5]. That’s pushed the house‑price-to‑income ratio from around 6 in the late ’80s to nearly 12 today. Home ownership is now out of reach for most young people, especially in cities. As prices rise in urban centres, younger buyers are being pushed into regional markets, exporting city unaffordability to those areas [6].

Yet many in my generation now own multiple properties. Their wealth, in no small part, stems from affordability conditions they largely didn’t create, but benefited from purely by the fluke of birth year.

Meanwhile, the rise of AI is already displacing white-collar entry-level jobs, the very roles that once offered young people a start. A future of early obsolescence for a freshly earned degree, followed by years of involuntary unemployment, looms. And with it comes a punitive social mindset: unemployment is seen as a personal failure rather than what it really is, a structural feature of a system designed not to provide enough jobs for everyone who wants one. Yet other societal and economic models exist, ones in which unemployment, and the inequality and fear it creates, are designed out entirely.

Today, the existential stakes for young people go far beyond economics.

When I was growing up, the big fear was nuclear war. That threat hasn’t gone away, if anything, it’s intensified. The Doomsday Clock is now set at 90 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to global catastrophe [7].

But now we’ve layered on more crises: climate breakdown, biodiversity loss, resource overshoot, and the destabilisation of Earth systems. In 2023, scientists confirmed we’ve overshot six of the nine planetary boundaries that underpin a safe operating space for humanity [8]. Just recently, Australia’s newly re-elected federal government approved new liquefied natural gas projects extending through to 2070 [9]. In the same week, the World Meteorological Organization warned of a 1% probability of temporarily exceeding 2 °C of warming within five years [10].

If we were genuinely on track to meet the Paris Agreement’s climate targets, such odds would be unthinkable. But we’re not. And it didn’t used to be this way.

When I was born, humanity was still annually consuming natural resources within Earth’s regenerative capacity, we were in ecological surplus. But by the early 1970s, for the first time in human history, we had entered ecological deficit, consuming at a rate equivalent to one Earth annually. In July, the Global Footprint Network increased that figure from 1.7 to 1.8 Earths. If everyone lived like Australians, we’d need four to five Earths! [11]. There’s no sign this trend is slowing. Year-on-year ‘green’ GDP growth, rooted in material consumption, is still treated by governments and mainstream economists as the unquestioned path to human prosperity, as if the planet’s resources are infinite.

And last week, the International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion that nations have an obligation to prevent climate harm and named potential legal consequences for those that fail to act. Although the case was brought by young Pacific Island advocates from Vanuatu, it’s not binding on Australia, despite our responsibility for around 4.5 per cent of global emissions once our exports are included [12].

The injustice is staggering. Young people didn’t cause the climate crisis. They didn’t design an economic and political system that locks them out of housing, secure work, or democratic decisions that entrench older generations’ lifestyles and accumulated wealth, all at the expense of younger people’s futures.

As the eminent Australian economist Professor Bill Mitchell recently observed, this is “the first generation in modern history to be worse off than its parents.” That’s a stark, short-sighted legacy today’s older generations are leaving behind. The stable, life-supporting systems younger generations should be inheriting are being liquidated in real time. And all wealth - financial, material, cultural - ultimately relies on those ecological foundations. What’s the point of saving and building your superannuation if the biophysical foundations of civilisation, the very systems that enable and sustain your wealth and wellbeing, are being steadily eroded?

So what are my generation, the Gen Xers and Boomers, doing about it?

Some of my peers are now entering early retirement. Yet their retirement plans include high-CO2 emission international travel and consumption-heavy lifestyles, behaviour utterly at odds with their professed climate concerns, and seemingly hellbent on exhausting the remaining global carbon budget, which, at current emissions rates, will be gone in under three years [13]. One climate-conscious friend recently starting retirement said, “Well, it’s too late to change anything now, so I’m just going to enjoy myself.” That, right there, young people, is how your future gets sacrificed on the altar of self-indulgent nihilism.

Then, given our ageing society, when they’re too old to travel, they’ll expect you to care for them in aged care. So you’ll end up juggling three casual gig economy jobs just to afford renting one of their investment properties for a roof over your head, until it’s time to wipe their bottoms. It’s a grim farce, and one built entirely on the privilege of birth year.

And it’s not as though the warnings weren’t there. The 1972 bestseller Limits to Growth warned that if humanity kept pursuing business-as-usual economic growth without regard to environmental limits, it could trigger global ecological and societal collapse by the 2030s or ’40s [14]. Fast forward to now, just five years out from 2030, and a 2021 scientific update comparing the original 1972 model to real-world data found we’re still tracking closely with that collapse trajectory [15]. The oldies ignored that warning then, when we had 50 years to act. Now, teetering on the brink, most still do.

So, where does that leave younger generations?

Don’t take your cues from older generations. Their worldview was shaped by a system that’s rapidly unravelling, one that insisted “there is no alternative.” Suggest something different, and you’ll likely hear: “That sounds like Communism!”, or “That’s anti-growth!”, or “That’s government overreach!” But fairer, saner alternatives do exist, ones fit for all 8 billion of us who share this planet. And they’re nothing like those tired caricatures. You just won’t hear about them from those who believe they have the most to lose from a more equitable world.

As one of the so-called lucky ones, I feel a responsibility to be honest: older generations are not going to make the necessary transformations. Oldies like me are willing and able to help, but we are the minority. The majority won’t lead this shift. There’s simply too much vested interest in coasting through cosy retirements while leaving the fallout to you. Too many are too comfortable. After all, most of their lives are behind them. Yours are still ahead.

I won’t offer a list of silver-bullet solutions. But I urge you to explore. Seek out thinking grounded in ecological realism, intergenerational justice, and global equity. Check out the growing post-growth movement. Some of the policies these frameworks propose once struck me as radical or politically unpalatable. Now I see them as essential: more ethical, more intelligent, and ultimately a better fit for our 21st-century realities than the paradigms that created this mess. As for those “intractable” political barriers, investigate new understandings of money, its nature, history, and societal purpose, and how this important public tool might be brought back under democratic control for our collective benefit.

You’ll face pushback, from the reputable, the powerful, and those offering sage advice to ‘give the markets time to adjust’ and urging patience, all while tightening restrictions on climate protests. But as Martin Luther King Jr. said, “This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilising drug of gradualism.” This is about safety and transformation, your safety, your children’s, and humanity’s.

Pushback, paradoxically, is a good sign. It means you’re challenging the comfort of those who benefit from the status quo. The more people who explore and embrace these new ideas, the easier, and safer, it becomes for those already in positions of influence to openly support and advocate for them. That growing momentum helps dismantle the stigma around so-called “career-limiting” views and paves the way for real change.

There is good news: the demographic tide is shifting. With each year, more young people become voters. With each year, more oldies exit the stage. Soon, you’ll be the majority, and with that comes the power to reshape this country’s laws, policies, and values for a just transition to a more equitable, dignified, and prosperous world that lives within Earth’s ecological boundaries.

But don’t wait. Start now. Begin imagining a world worth inheriting. Become active in whatever field calls to you, but ensure your activism includes engagement with federal politics, where the heaviest levers of a just transition lie, both domestically and globally. Democracy, after all, is a participation sport.

Learn. Speak. Share. Make the oldies uncomfortable. That’s how the change you need will happen. Urgency is now the name of the game.

Turn your year of birth into a lucky one, by shaping a future where luck no longer determines who wins and who loses.

References:

The Australia Institute (2024). The crushing cost of a university education: Hungry, sleep-deprived students loaded with debt. https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/the-crushing-cost-of-a-university-education-hungry-sleep-deprived-students-loaded-with-debt/

Soho Real Estate (2025). Sydney median house price in 1980 and 1989. https://soho.com.au/articles/how-much-was-a-house-in-sydney-in-the-80s

ABS (1987). Average Weekly Earnings, Australia.

YourMortgage.com.au (2025). Median house prices in Sydney. https://www.yourmortgage.com.au/compare-home-loans/median-house-prices-around-australia

ABS (2025). Average Weekly Earnings, Australia.

ABC News (2024). Regional house prices boom as city buyers move outwards. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-03-19/younger-buyers-pushed-to-regions-housing-prices-rise/102653458

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (2024). Doomsday Clock Statement.

Rockström, J. et al. (2023). Earth system boundaries, Nature.

ABC News (May 2025). Australia just approved Woodside's gas project until 2070. How could it happen? https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-05-31/woodside-north-west-shelf-approval-did-not-consider-climate/105347716

The Guardian (May 2025). WMO warns of high chance of temporary 2 °C warming in next five years. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/may/28/global-temperatures-break-annual-heat-record-next-five-years-world-meteorological-organization

Global Footprint Network (June 2025). Earth Overshoot Day 2025 falls on July 24. https://overshoot.footprintnetwork.org/newsroom/press-release-2025-english/

ABC News (July 2025). ICJ advisory opinion on climate change obligations. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-07-26/un-climate-case-puts-australian-fossil-fuel-industry-on-notice/105558100

The Conversation (July 2025). Only 3 years left – new study warns the world is running out of time to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. https://theconversation.com/only-3-years-left-new-study-warns-the-world-is-running-out-of-time-to-avoid-the-worst-impacts-of-climate-change-261229.com

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens III, W. W. (1972). The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books.

Herrington, G. (2021). Update to Limits to Growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 25(3), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13084