The Real and Imagined Rhythms and Clocks of Time

Action on the issues we care about needs an everything, everywhere, all at once effort. Too much to do, not enough time. Yet only by sacrificing the past & future can we be present for what is needed.

Time. Is it memory? Is it money? Is it a milestone? Is it fantasy? Is it now? Is it when? Was it then?

In every way time dominates my existence. From daily lists to future aspirations, quarterly tickets and monthly actions, yearly objectives as well as daily presence. If only’s of the past and when’s of the future. More than anything, the elusiveness of the present is ongoing. To actually live now means sacrificing the past and the present. I wish it was that easy for me.

Just this week we’ve seen the disgraceful and deceitful actions of a Federal Government with no plans, no policies and no principles - favouring the now over whatever the future may hold and dismissing what they said in the past. Without a plan, a policy or a set of principles what else can you do but what seems easiest right now? Maybe their cowardice can be explained as ineptness. A ‘leadership’ position held not so much because of something special or important about themselves, but the previous shamelessness of a group of possibly (somehow) even less principled people. What we said in the past be damned. Whatever happens in the future I’ll (but really you and your offspring) worry about then. A decision that has caused astonishment, outrage and despair now.

It’s hardly fair to only point the finger of disappointment and judgement at this Labor Government within a country seemingly beholden to the whims and interests of the fossil fuel industry. The Net Zero Tracker Stocktake for 2024 also this week provided its annual assessment of progress to this illusory future state aspiration. Most damning among a series of damning statistics was this one; “Although the number of credible net zero targets is growing, 5% or less of entities across states and regions, cities, and companies meet all our minimum procedural and substantive integrity criteria.” That is, we’re light years (one light year equates to 9.5 trillion km) away from doing now what our future selves hope they can say they achieved, on behalf of every generation of species both human and non-human to come. Every species. Every being. Forever.

I state regularly that I am an incredibly impatient and short to destructiveness. Those defects are usually not helpful as any disobedience to the status quo is identified as dangerous and threatening. In my defence though I don’t understand - as in I literally cannot understand - how anyone on this planet isn’t terrified about the rapidity with which the conditions on Earth - that have converged miraculously to create a goldilocks period for life now - are changing. I managed to finally bring myself to watch Johan Rockström’s latest update on the tipping points of climate change. “Earth system scientists, the climate scientists, are getting seriously nervous. The planet is changing faster than we have expected.” This was delivered before it was suspected we’ve crossed a seventh (of nine) planetary boundaries. I remember vividly being captivated by An Inconvenient Truth in a movie cinema in 2006. Hockey stick charts, perilous predictions and the consequences of inaction laid bare. My life changed forever seeing that film. Yet others are not. I literally cannot understand how that isn’t the case. Would attempting to explain red to someone who can’t see red be a similarly bewildering experience?

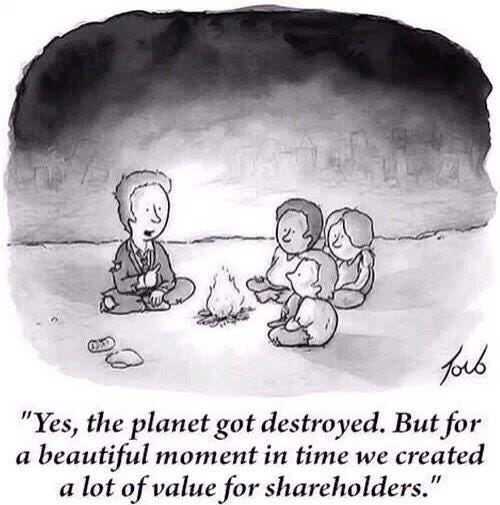

I’m not entirely naive though. 20 years of corporatising has allowed me to see how an increasingly deliberate obfuscation of reality reigns. Do this. Do that. Do something. Do anything. Do it all. Do what matters. Next time we’ll do what matters, this time we have to do what that uninformed and incorrect senior position person says. This year, this quarter, this (fortnightly) sprint. Overlay a commitment to maximising (short term) shareholder interests and the boundaries of individual myopic agency and we exist in a world where permission to think is limited to an entirely inappropriate timeframe and breadth of perspective. The inherent brilliance and strengths that each individual holds are reduced to a pin head, usually on the whim of that senior position person. Time is commoditised as efficiency, productivity and optimisation. Now is all that exists. Be damned philosophy, wisdom and principles of what actually matters nor respecting that living in a society with a sense of custodianship as links in the arc of time. Let’s just maximise (short term) shareholder value. It’s my job to be patient though.

That isn’t to say I want to bring out the acoustic guitars, light a fire and get folks sitting on logs (though I do). I know life is about motion, that time does represent some version of progress. Questions of progress emerge though. Progress to what? Progress for what end? Progress for what? None of these are easy to answer, especially in the heater skelter daily, pervasive and incessant busy-ness I face and you probably do too. Awful half day offsite (which seem to just be held onsite now) ‘strategy days’ abound. Ill-informed, without preparation, just turn up, wing it. If only these well-meaning but entirely absurd sessions had a sense of care, respect and dignity embedded within them. Maybe then they’d mean something. Maybe then they’d account for reality and what did actually matter. Instead though there is the unrealistic expectations that from this moment forth it’ll all be different. Then instantly into the next email, the next meeting, the next document, the next half day strategy offsite (onsite).

None of this is easy, I know. By creating Finding Nature I’ve had the remarkable privilege of having had hundreds and hundreds of conversations this year where the relatability to just about anyone and everyone working across the sustainability, ESG and impact fields has been remarkable, unifying and anguishing. All of us know enough is not being done now. Many are worried about their children’s future. Many are incensed about the lack of justice for non-human species who will be victims to humanity’s sprees. Many are outraged at the dissonance or outright lies from leaders in politics and business. 12 months ago I was in that state but alone and isolated. Finding Nature has bound me to others. From lost in the wilderness to connected in the struggle. I see my fear, incense and outrage in others. Strangely that is unifying. I’m not alone.

At 10:45pm, in the middle of putting this all together, I go into my three year old’s room just to see how he is. As I open the door he instantly mutters a moan I intimately know. I rub his hair, he rolls over. I keep rubbing his hair. The softness of his hair, the utterly familiar shape of his head, the sound of his breath. Instantly I am living both authentic time and objective time. I was there then with him while also entirely cognisant that before him awaits a life of increasing climate change, increasing species loss, increasing habitat destruction, increasing inequality, increasing challenges to access the right of safe and secure housing. “We really did have everything, didn’t we.”

It’s painful and enraging to be reminded of the deceit of this current Federal Government and what their decisions now mean for the rest of the life of an innocent three year old. He, and billions more, are who will have to live in the consequences of these manipulating phonies.

Incrementalism is Not a Strategy - Alison Ewings Wants Step Change

As long as I have worked in the corporate sustainability field I’ve known of Alison. Ever present in the world of financial services, she is one of a handful of pioneers in Australia who were doing this work before it was really a thing. I can only imagine that time in the late 2000s when even now in the first half of ‘The Decisive Decade’ it is still an arena not for the feint of heart.

In almost twenty years working in sustainability within the financial services sector there has probably been no concept more fraught with tension than that of time. The challenges of investing people’s money for retirement yet being judged on quarterly returns presents significant challenges for investors that inevitably flow through to the behaviours of the companies in which they invest.

This tension between time horizons is also ever present in internal change making efforts. Seeking buy-in from executives and investment decision makers takes time, as does creating the shared understanding required for achieving complex change. Yet even incremental improvements can be hard won.

Contrasted within this of course, is the rate at which humans emit carbon dioxide and its equivalents and the rate at which our consumption degrades nature. And the impacts of this are being realised at rates far faster than initially anticipated. When I first started working in this space I would never have thought that some of the impacts we are already seeing would occur within my own life time, but here we are.

Long to do lists of incremental items do not hold any interest. I find my core questions have evolved from simply asking “what is expected?” or “what are the gaps?” or “where can we start?” to be “to what end?”, “what will be the real world difference?”, “what will this mean in the broader system?” Don’t get me wrong, incremental changes can still be important, but only if they are clearly milestones on the path to the bigger changes required.

These musings have led me to a number of working hypotheses (part of the role of the sustainability practitioner is to be alert to the need for review so I hesitate to call them conclusions).

Low hanging fruit is overrated

Increasingly I am of the view that the notion of low hanging fruit is a distraction. The most impactful and important work is complex and time consuming, rather than delay it in favour of the easy things, I now wish to dive headlong into the complexity of the game changing elements.

These elements are often about capacity building, garnering critical mass and brokering difficult or unexpected coalitions. Doing this successfully means there will be more of us undertaking the work required and the low hanging fruit will inevitably be picked up on that wave, but the wave needs to be my focus.

Be bold but also patient

Big changes are required but we also desperately need them to be enduring. Big targets and splashy initiatives may seem impressive, but are ultimately no match for an organisational compass that is steadfastly pointed in a different direction. This seems to me to be the pre-requisite for delivery.

Having a policy approved is one thing, having it championed and be well understood, supported by tools and road tested against future scenarios takes time. Better still having it hardwired into processes, backed up by KPIs and reported appropriately sows the seeds of longevity. Importantly, it also reduces the effort required to defend it further down the track, including when that work is inherited by other practitioners in the future.

Culture change requires consistency, we need to dig in and do the work required to really embed.

Systems thinking is no longer optional

The road is fraught with unintended consequences. Again, the time taken to consider these up front can yield dividends later. Understanding the wider context and interdependencies helps you identify the key barriers and the best levers for change.

It can also help you work more creatively, join dots differently and, where done in coalitions, reap the benefits of truly diverse perspectives and talents. The work to do this and create this shared understanding takes times, it can also take courage, trying new ideas and bringing together a complex array of stakeholders. As I’m sure you will have recognised in the themes here, I see this as time well spent.

And when all else fails…..

Acknowledge that you are in a petrie dish.

For the most part these challenges haven’t been solved before and every scenario is different. Often the challenges - especially in areas like biodiversity - are highly localised and organisational cultures will be different and therefore so too must be the responses.

Know that you will get things wrong and that is okay, provided you pivot and commit to correcting your course. Experimentation is crucial. At a time where there are more frameworks and compliance obligations than ever before we need to retain agency for our work and our decisions. Tools are just that, we can’t abdicate strategy to them, we have to throw ourselves into the experiment – head and heart.

And finally,

We need to think about the practitioner as well as the practice

What I mean by that is that while there are lots of support networks and industry associations aimed at specific challenges or actions there is not enough of a focus on developing capability within practitioners generally. The focus, in my experience, has typically been on technical knowledge and less on the skills that underpin securing successful outcomes. Skills like effective change management, facilitation and negotiation, learning how to identify and seize opportunities for influence (also known as getting the timing right), how to build effective coalitions (more synonymous with the art of the hustle than you might think) and of course building our own resilience.

Sustainability has often been a lonely road, especially in the early days (I refuse to use the word journey!) The more support we can give to fellow travellers the better, and the faster we will get there.

What You Don't Know Does Harm You - Nina Jankowicz Is The Valiant We Need

Nina Jankovich is a world leading expert on the mysterious and imperceptible world’s of mis and disinformation and how information in any and all forms can be weaponised in nefarious, poisonous and pernicious ways that degrade social cohesion, democratic health and how many people - including myself - perceive and make sense of the world.

Nina's personal experience after being appointed by US President Joe Biden to become the Department of Homeland Security's first Executive Director of their Disinformation Governance Board is a harrowing first hand account of the dangers and threats individuals face in a culture divided along ideological lines and where multiple realities of truth exist. In today's conversation we go into what all of this was like for Nina and her loved ones, and how she continues to live in the shadows of the consequences of the seemingly deliberate and dangerous actions of many.

Disinformation - what's that got to do with me? Well, the more I become familiar with and learn about the scourge of disinformation the more I wonder about my own judgement and skills. How do I detect what could be untrue, and what gives me confidence I'm able to consistently and accurately discern and distinguish the information I consume based on the rivers of it I'm exposed to day in day out? There's really no excellent answer to that - my own beliefs and stories that I'm educated, that I do know truth from lie, that I can really tell what is off the mark compared to entirely spot on.

It Always Takes Longer - Cat Long Juggles Roles, Identities and Time

I met Cat through a good friend, and the idea that she left a major corporate to have a crack at leaving a mark in the world in an entirely different, new and speculative way spoke to my soul. Four years later, she’s doing and done it.

Based on no evidence whatsoever I suspect that the words ‘time’ and ‘busy’ are the most commonly used words in any work environment. I constantly catch myself saying ‘I’m busy’ or ‘I don’t have time’ as if that’s a good excuse. The reality is, if something is important, we can always make time.

So naturally when Nathan asked me to write my thoughts on time, my first inclination was to say ‘I don’t have enough’. Then I stopped myself and thought – maybe this is an opportunity to challenge that belief and maybe even enjoy the challenge.

Nonetheless, I am busy (I am a startup founder & CEO, wife and Mum of a two-year-old) so I’ve decided to Timebox this essay to 25 minutes. Why 25? Well I’ve recently started using a tool called the Pomofocus based on the Pomodoro theory that you are most productive in 25 minute blocks. It’s super simple and super effective – check it out.

Everyone in the world has a relationship with time - our days, weeks, years and lives are finite in time - so the following represents my personal experience and nothing more. For me, time is often a stressor - running late is stressful, running out of time to complete a task is stressful, getting older can feel stressful, the race to mitigate climate change (more on this later) is stressful. Which got me thinking, would we all be happier if we couldn’t tell the time? My toddler can’t read the time and he's blissfully happy (mostly).

But the reality is, it’s impossible to avoid time and even if we remove clocks and deadlines, time still passes and is evidenced in nature by the rising and setting of the sun, our circadian rhythms, the seasons and physical evidence of ageing (objects and animals). The only thing we can control is our perception of time.

We’ve all experienced time going fast when we’re having fun or in a flow state and dragging on when we’re bored or waiting for something. Obviously, the speed of time doesn’t change in either case, but our experience of it can do drastically. To explore what’s driving this slowing and quickening of perceived time for me, I thought I’d analyse the chapters of my adult life.

Uni Days and Years

For me, these three years elapsed at perfect speed. I don’t recall ever thinking ‘time is running out’ (except in those few weeks in the lead up to exams), and I believe this is because I was (A) blissfully naive and unencumbered by pressure to do anything but pass exams and (B) in the perfect equilibrium of having fun, learning and looking forward to the future i.e. I was present.

Early Career London Corporate Days and Years

Much like many graduates I followed the traditional course of finding a solid, well paid corporate job and ended up in management consulting. The speed of time in this period was volatile. I lived for holidays and weekends which both zoomed past, Sunday blues were real and Monday to Friday could feel like three days or three months depending on the project I was working on (I remember a particularly bleak assignment in Edinburgh in mid winter, flying in and out four days per week and my only social interactions were with my German manager). My working days regularly ended after midnight, which meant personal time was limited, but it was worth it (at least in the short term) for the lifestyle, career progression and relationships the job afforded me. Eventually enough was enough. I wasn’t ready for five more years of the treadmill, so I moved overseas

Sydney Expat Days and Years

Oh the glory days! Looking back I can’t believe how much I would cram into a single week - I was the fittest I’d ever been, doing well at work (not hard: in house strategy is 10x easier than management consulting), building lifelong friendships, launching a side hustle and exploring everything that Sydney and Australia had to offer. ‘Two years abroad’ passed so quickly the thought of moving home barely crossed my mind. Looking back, the years went so fast, the weeks were steady but the midweek days often dragged. I loved my lifestyle but my work lacked purpose.

Becoming a Climate Entrepreneur Days and Years

My working life took a massive pivot when I decided to launch my startup, Trace, with my friend Joanna in 2020. All of a sudden, my career had meaning and I was learning more per week than in any year prior. These three years moved at a beautiful pace but it’s impossible to know if this was because of my new career and new relationship with my now husband or because of COVID. All of a sudden life felt simple: I had fewer choices, endless time for new hobbies (has anyone done a puzzle since COVID?) and exercise was a pleasure not a chore since it was the only activity permitted outside. For many, the lockdown years were very painful so I count myself extremely lucky to have loved every minute.

Balancing Founder and Family Life Days and Years

Fast forward to 2024 and life feels more complex than ever before and my relationship with time has changed drastically. I deeply feel the pressure to make every minute count because I want to be a good wife, Mother, co-founder and leader. I know I can’t do them perfectly concurrently (24 hours is still 24 hours and sadly I’m not one of those leaders that only needs 5 hours sleep) but that doesn't mean I don’t want to. I’ve become more disorganised (in my personal life), highly task oriented (at work) and frankly a little anxious (not something I’ve experienced before). As a result, I’ve started learning about productivity hacks, Flow States and started having leadership coaching. Time has never felt so precious and I’m conscious it’s slipping away. And to top it off, working in Climate is a constant reminder that if we don’t act fast, there will be no future for our grandchildren.

Based on my amateur analysis of the above, I’ve concluded that my experience of and relationship with time is a function of my expectations versus reality. Time moves at a lovely pace when I set myself goals I can and do achieve which applies to short term goals (my daily to-do list) and long term life dreams.

I started this essay with a simple goal of writing 800 words in 25 minutes. It took 75 minutes to write 1100 (excluding editing). As a result I feel stressed because my day is slipping away. But at the same time, one of my longer term goals is to write more and be more present and this exercise has offered both.

Rather than be frustrated that I’m ‘behind time’ for the day, I am going to pat myself on the back, reprioritise my to-do list and consider this a productive day.

Everyone knows life is short, but in my view, it’ll feel even shorter if I put too much pressure on myself to make every second count. I’m happier when I’m present and don’t fight the clock.

Illusory Perspectives of Time - Patrick Nykiel Rings Alarm Bells

Patrick is another that got away in my day to day professional life. A polymath and cogitator, I have a reverence for Patrick’s approach to living, his philosophies and knowledge base. From the depths of contemplative conversations to deeply technical scientific explanations, he is someone wonderful to spend time with.

The theme of time is one which emerges seemingly everywhere in the environmental domain - notable for the diverse ways in which this intrinsically ephemeral concept arises. Reflecting on my experiences an aphorism from the opening scenes of the Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy comes to mind:

Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so.

While stated in defence of day drinking and with the imminent destruction of the Earth to make way for a hyperspace bypass, it does seem oddly appropriate. Appropriate too in the absurdity of modern environmental practice. Scientists of all stripes have been ringing alarm bells of the imminent climate change threat since the 1960s and yet the same patterns of thinking, with the same problems and the same outcomes seem to remain. The revolutionary 1972 Limits to Growth book used modelling to warn of the dangers of unconstrained economic growth. The outputs of the many models underpinning climate scenario analysis today are remarkably similar and certainly tell the same story.

Before I got lost in the great machinery that is the finance industry, I used to claim philosophy as my home discipline (or as close to a home discipline as a generalist can claim). I spent much of my time deep down epistemological holes chasing illusory terms like positivism and transdisciplinarity. Time crops up a lot down said holes. Most of those I learnt from would certainly agree Douglas Adams was on to something. The linear notion that time somehow moves calmly A->B->C is entirely in our collective consciousness. Western society is critiqued as relying upon the conceptions of teleology (the conception that things have to have an intrinsic purpose) and positivism (true knowledge being the elevation of facts derived through empirical observation).

If we consider that all things have a purpose, everything that happens to said ‘thing’ must progress it toward that purpose. And if the yard stick for progress is the continual advancement of knowledge (but only that which is factual and demonstrable) then we start to see why all facets of time become linear. Society is always moving from a position of the primitive to the enlightened. Superficially sound, but leaves no room for the consideration that things might regress and indeed, with this characterisation of time, it becomes impossible to even entertain such a notion.

Perhaps more troubling is the recent rise in anti-intellectualism. Uncontentious notions being captured by powerful interest groups and made political. Social media gave everyone a bullhorn and suddenly facts are not defined by truth but by clicks, likes, shares and upvotes – in other words, popularity. We still measure progress against the past but what we know about the past has become cloudier, in some cases for sale to the highest bidder. With generative AI looming, I wonder how long the dominance of 'fact' can continue. Few could argue this being progress in any socially beneficial sense.

For some time now this has been my job, to gaze into the crystal ball of scenario analysis and ponder what might be – Alarm-Bell Ringer In Chief and Professional Pessimist at some of Australia's largest companies. The way that I bend time in this setting takes me a long way from my roots, wielding t as a mathematical dimension, alongside latitude, longitude, and elevation. I shift raw climate model outputs for insights at impossibly fine scales – from hours to days when scientific standards expect decades. Absurdity reigns on occasions where I have been asked for what amounts to a street level weather forecast in spring of the year 2050. Yet, with all the data in the world there is currently no reliable way to know whether floods will become more or less frequent across any part of eastern Australia. I can only say that snow in the Melbourne CBD will continue to be unlikely.

The answers for the future I provide come from the reconstructions of the past. If you gather enough weather records together you can infer what was. Melbourne last saw decent snow in 1951 for instance. This data can be enough to tell you what could be, assuming no change since 1951, which of course it has. We do call it climate change for a reason. As a result, I don't see time as a line anymore, more like an evolving echo of what came before. Even in a mathematical sense, I work with synthetic reproductions of a span for a single given point in time, randomly iterated from 30 years of input data out to 50,000 years. Some newer models take that 30 years and project it forward, creating echoes of echoes, the data is no longer 'real' in any sense but no less valid.

In some ways my problem as an analyst becomes flipped. Instead of the steady background tick counting down toward environmental catastrophe that seems to pervade our profession, from the annual ratchet of the Keeling curve or cyclical rise in global average temperatures, I hear the cacophony of too much time, too much data and too much effort sacrificed to the endless pursuit of quantification. Does knowing exactly how many houses will flood/burn/be blown to pieces in the average year now and in every subsequent decade for the next 70 years actually change the action we need to take? Have I been captured by the base social imperative to collect nuggets of knowledge in the pursuit of progress?

For the sake of my wellbeing, perhaps it is best not to think too much and instead focus on the relationships around me and the people who are slowly assembling, the army of the willing, relentlessly nudging our decision makers in what we hope to be the right direction. Perhaps I should take a cue from some of the great reinforcing cycles of the natural world – the relentless action of water on a stone can carve through mountains. But is there enough time?

Blowing The Whistle on the Climate Crisis - Regina Featherstone Won't Go With The Flow

Regina Featherstone is a Senior Lawyer at the Human Rights Legal Centre and co-authored their recent publication Climate and Environmental Whistleblowing: Information Guide. On Regina, well you know when you meet someone who is clearly a star rising - articulate, steady, eager and virtuous - that is Regina. We didn't have the time today to get into more than just this guide but her background is immensely impressive.

Regina has worked in top corporate law firms but also in community legal centres where she has focussed on migrant worker exploitation and workplace sexual harassment, and for several years worked as a solicitor on Nauru assisting asylum seekers to secure refugee status. To do that work and what she has worked on since, speaks of an incredible moral fibre and a courage that is not conditional - something we talk about in this episode.

And this episode - you'll hear it in the opening, but I was nervous speaking about this topic. Whistleblowing is a contested topic - the actions of the dobber, the mole, the nark, the rat. Personally I don't really get it - I don't see why anyone would go to such an extent to create such danger to themselves if there weren't serious and credible evidence of wrongdoing. But it's often how whistleblowers are perceived that prevents wrongdoings from coming to light.

Now & Then Plus The Inner & Outer Work - Time Finding Nature with Adam Bumpus

I’ve never met Adam in three dimensions. A special relationship formed in a special time - during Covid when I was in a strange phase in my career attempting to unlock a bank’s capabilities to become a serious energy market player and while both of us were becoming fathers for the first time. Adam is part intellect, part dreamer, part intense energy, part philosopher, part creator, part educator but entirely whole-hearted.

Nature works at such hugely vast time variations. From the evolution of our planet starting 4.5 billion years ago to the rapid and exponential growth of single-celled organisms. From the lifespan of a bee to the gracious ageing of a bowhead whale.

For our own species, time horizons change too. Although time on our planet is linear and absolute, our perception of time alters moment by moment. It seems to naturally speed up as we age, goes by more quickly when we are having fun, or drags terribly when doing the tasks we dread. Those of us with kids know fully well that the days are long, but the years are short. Its relative nature is very real.

Climate action and time

Working in climate change for over twenty years also has its own specific relative time horizons. Another year on and another UNFCCC Climate Change Convention goes by (the 29th annual meeting is in 2024), another record-breaking year of extreme weather, another twitch in the economy making companies vacillate on their targets and action on climate change. Each event is a moment in time, and with each passing hour, day, week, month (depending on how anxious I’m feeling about hitting a climate tipping point), I find myself asking: what have I done so far? What has been my contribution? Where have I really made any meaningful impact on this issue? How much time is left to make that difference? What should I do next?

It seems the velocity (simply calculated as distance over time) for change and action on ensuring we have a liveable planet is still too slow. Velocity is critical for change because it denotes a shift in state over time and creates momentum to keep going. For a long time in the scientific world, we have been giving ourselves planetary deadlines for climate actions. The translation into policy and corporate action has been much slower. Somehow the generous timeframes scientists have offered are too slow for policy makers and corporate actors.

Net zero by 2050 is finally almost universally accepted. But we see companies and governments reneging on their emissions goals precisely because they are running out of time to reach them and the time pressure of a quarterly statement and multiple shareholders working on different time frames. This ranges from accumulation concerns such as when will I get my dividend? Or when will the company exit and get my pay out? To the very real practical concerns of can I pay my rent or mortgage this month combined with real existential pain of my existence when regular payments become hard to make? In a world where time and money are so intrinsically connected for so many people (an hourly wage), the question is very real of what do we have to cut back to live?.

There are 274 weeks until January 1st, 2030. We will have needed to halve our global emissions by that point and be well on our way to net zero with plans to achieve a carbon negative from 2050 to 2100. So how are we tracking on that timeframe?

The good news is that from an energy and emissions perspective we are on the right path and emissions have tipped into decline in 2023. Maybe just in time given the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said 2025 was likely to be the required tipping point. But the corridor for us to achieve a truly climate safe world that is inclusive and just for all homo sapiens (rather than just a few specific socioeconomic categories) is narrowing each passing moment (see the wonderful recent paper on this from Joyeeta Gupta, Xuemei Bai, and my former PhD supervisor, Diana Liverman).

So how can we approach the time we have each day with how we view and understand the nature around us?

Moments in time with an acute specific event, realisation, or awakening - sometimes from a deus ex machina (not necessarily a motorbike but an unexpected saviour to an improbable event that brings order out of chaos) - can fundamentally shift our view of ourselves and our role in the world, and by doing so our view of what we do with the time left. It can help us bring forward the importance of an idea or initiative that could otherwise bubble along in the background for years. Suddenly the small voice in our head becomes the most prescient thing for us to think about and, most importantly, take action on.

Balancing the longer- and shorter-term timeframes

So how do we in a personal and organisational context balance the requirements of creating ‘wins’ in the short term, but maintain resolution to do things that take more time but will ultimately have more impact?

I live in a few professional contexts. As professional consultants we are tasked with providing answers and solutions quickly. As practitioners, thinkers, and educators of nature and climate we are responsible for creating new ways of being and doing to support a safe and just climate future.

Balancing our deliverables with “listening and innovating in the Emerging Future”, as Otto Scharmer of MIT U-Lab puts it, is the daily challenge and opportunity to drive change. All of those small actions contributing to the longer game, sooner or later, hit an inflection point for both our daily work and impact on the world around us.

How do we maintain this balance?

This has to start with ourselves. Personally, the way I have seen to do that is to balance the requirements of daily work that are needed to financially support myself and my family, whilst also holding space for work that takes longer to realise but can create potentially wider, longer-term benefits. For example, a proposal or report needs to be written and delivered today, but a programme that can engage and educate a wider audience on the role of personal, economic, spiritual, and planetary connections takes a longer time to gestate and deliver. Both need to happen simultaneously.

This means always having more than one professional task on the go. As a person with ADHD this naturally fits (focusing on solely one thing for any length of time is the creatively inimitable challenge us ADHDers face). I’ve always consulted, and had an academic role, and a startup, plus hobbies and now a growing family. It is a challenge and often one professional element must take a backseat, for a period of time, to enable another to complete or emerge, or just simply to make sure our family is secure and safe.

Not everyone wants to live with multiple projects on the go (it brings with it many difficulties and stressors), but it does give me the perspective to hold both the short and long term for our connection to nature and climate in the same space.

To bring colleagues along the journey of connecting the immediate wins with longer term ambition is slightly different. It is about providing the small interstices of time and space that give them the opportunity to think about how the thing we are doing today contributes to the bigger picture. As leaders in organisations, I think our role is to foster a process of consciously reconnecting our daily work with the longer term horizon, who we as individuals and a society want to be, and how we as organisations contribute to that future. This is the true expression of how our agency to reconnect can contribute to shifting the structures that have disconnected us from nature over the last 250 years.

For much of corporate Australia, there is latent passion, energy, and enthusiasm in middle management to take action on climate change but few opportunities to realise this in daily work. If we could unfreeze the corporate middle, velocity for climate action across our economy would be unleashed and enable faster action. Both for compliance under the emerging regulation, but more importantly to foster the analytical, creative, and self-efficacy skills that the World Economic Forum has noted are critical to the next stage of economy building.

Many of the barriers and opportunities come back to our own sense of self and who we are as individuals. Most of us who have followed a path for educational certificates and letters after our names, accolades and awards, titles of a professional role, our standing in society (and now in social media), eventually realise that these acquired things do not fill the holes inside us. To do that we must come back to ourselves, our “fathom long body” as the Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield would remind us, which holds the answers for where and what we need to do. Time, again, is a critical component in thinking through this. A new technology for our company can promise we’ll do more work faster and better, a new job title gives prestige and energy to take new steps, a new senior appointment into the company again gives us a boost and enables more. This can be true, and they are part of creating the solutions for our planetary problems, but they must be grounded and titrated daily with a personal journey which acknowledges the balance between our egos and what we as individuals of a species connected in an ecosystem really need.

So, what are the components of time that we need to focus on?

Firstly, finding the small moments in our day where we can find our own nature. To notice that we are connected to everything around us. We are made up of cells, each of which contain our entire genetic blueprint and evolutionary history. That the plants in our living room or corporate lobby (if they are real) are breathing out the oxygen that we breathe in. Taking these small moments helps reground us and be present in the moment.

Secondly, taking the time to sit and experience what part of nature and climate action you want to influence. In our personal and professional lives there are ways we can act, groups we can join, friends we can make to activate or influence a change. Two simple exercises to capture this is 1) to write your own obituary of how you want to really be remembered, and 2) ask yourself what would you do if you had four months to live, then four weeks to live, then four days, and then four hours. Who would you spend it with? What would you do? Why would you do that? Memento Mori the stoics called it. It's just giving perspective to manage and balance time on what really matters to you over the long haul.

Finally, taking action to join something or do something in the direction of reconnection. And it doesn’t have to be huge. Small, dedicated groups bend time by altering the zeitgeist. Movements take years to build and then make huge differences very quickly to disrupt systems. Social and environmental movements can be exponential. They suddenly change our relationship to nature because of the work put in over time; they turn a half-covered lily pond one day into a fully covered lily pond the next.

Most importantly, to sustain ourselves and create change, is to belong. Time stands still when we feel we are contributing to something bigger than ourselves, with people we respect and care about. Connecting oneself (our literal mortal time) with our purpose on how we can contribute to the world (our ‘beyond a lifespan time) is how systems change. And by taking the time to work through our personal journey in the context of planetary needs is how we can start to belong and reconnect with the nature within us, between us, and around us.

It’s an incredibly exciting time to be alive; a mere blip in the 4.5-billion-year history, but one that is pivotal to how humans decide to reconnect and coexist as nature rather than masters of it.

The Animals Do Not Want To See Us - Satyajit Das On The Perils of Wild Quests

Satyajit Das - or Das - is a man who's worn many hats. Financier, author, traveller, speaker - a strenuous protagonist for evidence and fact. He's a man who wants to understand and take into account the reality of a situation and to look deeply into the meaning of that information, no matter how confronting, surprising or alarming.

Das came to Australia from India in the late 70s, and a career in banking followed, until he had some unexpected life changing expeditions in nature - one in Zaire, now Congo, and the other Antarctica, which seems to have altered his relationship to work and living. He famously predicted the impending global financial crisis in 2006, before being named as one of finance's most influential thinkers by Bloomberg. He's written a tonne of books along the way, and he's on the show today to talk about his most recent - 'Wild Quests'.

I really enjoyed this book, and I have been affected by its contents as well as Das' previous work, especially that of Banquet of Consequences. Under all of our technological progress are worldviews and stories that we are still above and apart from nature, that we can elevate and innovate our way out of whatever the latest dilemma or disaster is. This book tells of the heart wrenching ways by which eco-tourism is negatively affecting remaining pristine landscapes, continuing to drive up emissions through al the travel time and with uncertain and unclear local social and economic benefits.

Hope Springs Eternal For Rohan Shah - Right Now, Right Here

I didn’t know Rohan until the launch of Finding Nature. Suddenly he was there, arrived back from Berlin and looking to shift his future. What a person to come into my life. What a gift of this endeavour. A career investigating integrity and a life exploring the depths of the inner world, Rohan is a seeker.

In this world of quantification and calculation, we hold onto the few constants that we can rely on. Time tends to be viewed as one of those constants. Unfortunately for us, the concept of time is not as solid as we like to believe. Through the lens of quantum mechanics, consciousness studies and other ‘emerging’ fields, the concept of time is incredibly complex. In fact it is increasingly questioned if the concept of time is ‘fundamental’ at all. While that may feel far fetched and impractical, a simple experiment that everyone can do, quickly brings the concept of time into focus.

One can check their own experience and stay true to it, like a real scientist relying only on their current direct experience, without bringing in any assumptions or other learnt data. Experience is the only ‘thing’ that is directly verifiable in our awareness. That is, everything that occurs, happens in our own experience. When I explore this, I inevitably reach the conclusion that everything is happening in this moment. The only moment that exists. By way of example, even this morning’s breakfast is simply just a memory, or to be more precise, a mental image in the form of thought, that is recalled in the current experience. There is only a process of thinking that gives it a sense of tangibility and to verify ‘breakfast’ happened. If one has breakfast with a partner, we can then corroborate that experience with the other and make the collective assertion that, ‘we had breakfast this morning, which occurred in the past’. But that view of the past, can only take place now, through the lens of our current experience.

Perhaps the best way for me to grasp the reality of time is through analogy. That our perception of time is more like a ‘movie’, a series of events, shot at different times, spliced together to create a logical sequence of seemingly concurrent events. It appears that time is sequential, however just like in the movie, the actual events take place over days, months or years. These events all conveniently fit within 120 minutes, given that is (or was) the acceptable attention span of our movie culture. Through the lens of our thinking mind, and its perception to relativise the ever changing nature of our world, the thinking mind conceptualise events and time as a way to bring it into coherent order.

Why does all this matter? Well, to be honest, it probably doesn’t and I am surprised you have read this far. It is a somewhat abstract formulation that only a minority of folks, meditators and armchair philosophers are willing to entertain, let alone pay much attention to. But the important part is, the recognition that our perception of time colours all experience. This one concept influences all of our thoughts, feelings, decisions and actions. And it is the same process, that often assumes causation. That one thing leads to another. But that is not always the case, given we often do not have a total view of our experience. Our subconscious, collective unconscious and societal conditioning, means that our blindspots are often so large it makes it hard to see the forest from the trees, particularly when it comes to something as abstract as time.

Take the impacts of colonisation, poverty or war as examples. A progress narrative is so dominant in our culture that one need to ignore a lot of basic facts (through cognitive bias), to somehow emotionally reconcile with the current state of play and the privileges that come along with it.

So how do I come to terms with time? I sit in an ice bath once in a while and watch how fast time stops. Five minutes can very quickly feel like an eternity. Enough time to reflect on my own perceptions of another agonisingly slow process. Climate action.

I came across an article detailing the third IPCC report in circa 2004, I read it with concern, and thought to myself: ‘if this is true, we are in deep deep shit’. I observed the importance of climate change ebb and flow, with a wave of optimism building circa 2007, only to be squashed by the 2008 global recession. I remember the consequent total failure of the Copenhagen 2009 COP and my dismay of Australia’s climate position which essentially was: ‘we will only do something, if everyone else does something first’.

It was around 2014 when I started studying renewable energy, that I remembered my university lectures on ‘triple bottom line’. An old concept from the 1970's, that is necessary to adopt from a climate risk perspective but also represents the problem of trying to put a dollar value on everything, including the unquantifiable intricacies of our anthropogenic view of nature.

I perceived that history repeated itself in 2019, living in Berlin which was home to the largest of the global climate demonstrations, buoyed by incredible optimism that the moment ‘had finally arrived’, only for the momentum to be somewhat hemmed by the Covid pandemic.

Returning home to Sydney and its award-winning Green Star buildings, I am often dismayed at the slow parochial nature of climate inaction in the Australian landscape, but also across the world. I often need to remind myself that I have two hats: an ‘impatient' and a ‘patience’ hat. Knowing when to wear which hat, is wisdom that I am still trying to cultivate. The paradox of urgency and patience is underlined as a government that made election promises of ‘no new extinctions’, continues to approve new coal mines, inexplicably weeks before it hosts a Global Nature Positive Summit. A thought arises: the head winds of history indicate that ‘it is much easier to destroy something (an idea or movement), than it is to create one’. Meaningful change is hard and indeed takes time. Meeting people where they are emotionally are on a subject, also helps. My ‘patience’ hat comes to the fore.

I have also learnt that integrating our past helps us break out of old patterns and into new ways of being. This is also rings true for the collective. The only reason I have any ability to reflect, is with deep gratitude to our ancestors, from who we can learn a great deal. Indigenous cultures have a different perspective of time and they often perceive time in cycles (seasons, lifetimes and ages), rather than a linear advancement towards ‘the future’.

A book called, ‘A Short History of Progress’ by Ronald Wright, strongly influenced my early thinking on climate matters circa 2006. Wright outlines the "progress trap" that refer to innovations that create new problems for which the society is unable or unwilling to solve; or inadvertently create conditions that are worse than what existed before the innovation. He details an example in the book, that advancements in hunting during the Stone Age (such as rocks, to stone axes and finally to forcing a herd of animals off a cliff), allowed for more successful hunts. This led to more free time during which culture and art proliferated (cave paintings, bone carvings), but also led to extinctions. It was an influential book for me, as the author detailed civilisation collapses of Easter Islanders, Sumerians, Mayans and Romans as a result of living beyond their resource boundaries, which still rings true some 20 years later.

Those elements of unmitigated capitalism, consumerism, ceaseless technological ‘enhancements’ and a stern belief that markets will somehow magically get us out of a polycrisis, feels new but also strangely familiar. No doubt courageous actions of CEO’s and investors are required, but they will generally still be pulled back to the herd by definition of competitive comparison. Climate risk metrics are far too often short dated, rather than factoring longer term intergenerational equity and socially based outcomes. Regulation will always be a lag indicator and enforcement penalties generally pale in comparison with EBIT. Another strong attribute of the mind that is constantly judging and comparing, of what is better and worse.

So perhaps one solution is to come out of mind, and into the heart, which resides in the present moment. From this place, my belief is that we can still turn what feels impossible to possible. I don't know exactly how it will work, but what is important for me, is that we feel called to try do things differently. Perhaps breaking away from well-worn paths, embracing the unknown, together with radical collaboration moves the narrative toward achievable and socially just outcomes. This also requires courage and willingness, if we are to bring about a widely accepted new normal in an appropriate timescale.

In my personal experience, in order to have courage, we need that which guides us through the unknown, to let go of control. If control takes hold, through money, power or self-interest, it is likely that circumstances will continue to perpetuate itself. I suggest that deep trust in collective efforts and wisdom is the path to change. Could our insistence on knowing the future or thinking we already have the answers be the very thing preventing us from creating it? Implied in ‘not knowing’ is the ability to compassionately see beyond individual missteps and the inevitable imperfections of our world’s inhabitants.

Interdependence of the individual and society is paramount, just as nature and all living beings on this planet are interconnected. This stands in contrast to society’s current course of trying to technocratically outsmart nature or dominate it. That is how we got here, and in my opinion will not be how we get out. We find ourselves in paradoxes, where we need to reinvent, or more precisely, return to our being.

Ancient traditions might give us clues. Perhaps we need to start listening rather than talking. Using our hearts instead of our minds. From that genuine place is where true creativity and coherent innovation resides. We already see it in solutions that resemble a returning to our past. Biomimicry, biophilia (design), natural materials, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, preventative healthcare, circular or sharing economies, traditional land and water practices, returning emphasis on ritual, trust in the collective, non-hierarchical organisations and living intrinsically connected with nature are just a few examples. We know and hold all of this in our current direct experience. When one truly appreciates nature (say, the sight and smell of a single flowering bud), we allow ourselves to be transported to timelessness through the intuition of what is beautiful, truthful, just and loving. Hope springs eternal. I heard somewhere that English is 75% nouns and 25% verbs, but in ancient languages the proportions are 75% verbs and 25% nouns. Hope is indeed a doing word, and it is only possible in the present moment.

Vibrancy and Vitality - Dr Dominique Hes Makes Regenerative Futures

Dr Dominique Hes is an author, educator, policy advisor and regenerative thinker. She certainly fits the bill of the change makers and paradigm busters I'm curious speaking with as part of my own quest to understand and contemplate and experiment with how to go about making the world a healthier, safer and more beautiful place.

There was a lot that I took from this chat with Dominique who for nearly three decades has pursued more than just sustainable futures but has been investigating and experimenting in ways by which to bring about real transitions and transformations. Her career, achievements and ongoing work are testament to the breadth of her curiosities and interests, but also her strengths and domains of knowledge. At the moment she is an Advisory Committee Member of the Federal Environment Minister's Circular Economy Ministerial Advisory Group, the Chair of the Board of Directors at Greenfleet and an adjunct fellow at Griffith University. She is deeply connected to and working with community driven regenerative projects across housing, agriculture and urban landscape renewal.

Dominique is a distinguished guest and someone who for two decades has been on the forefront of regenerative development - not regenerative in the sense of a framework or tool but a fundamentally different frame of understanding and being in relationship with self, each other and country - to be of service and generous in how you show up to support and cultivate vitality, vibrancy and longevity. This mindset and posture can seem untenable with what too often seems like a fixation on value extraction, resource optimisation and perpetual growth. Part of today's chat is about the limitations of finance as it is currently constructed, the inherent constraints that exist with what and how monetary systems value life and relationships and reality, but also how worrying too much about those limitations and constraints can become a blocker for progress.

Brett Morgan Counts The Climate Crisis In Weeks

If you work in corporate sustainability you probably know Market Forces. A trail blazing organisation that has held fire to many, especially those in the financial services industry. Brett lives there. Pushing, prodding, escalating, manoeuvring, acting, advocating. Attempting to play four dimensional chess while having a front row seat on the glaciality of meaningful change in those sectors.

If you had to guess your lifespan in terms of weeks, what would your guess be?

4,000 weeks. 4,000, measly weeks. That’s the correct answer, assuming you live to the age of 80.

When asking others this very question, Oliver Burkeman – author of the aptly titled 4,000 weeks – understandably received a range of different responses, one answer “in the six figures.” While my own guess was far short of a six-figure answer (100,000 weeks is nearly 2,000 years, by the way), I was still shocked at how insignificant 4,000 weeks really is. I tend to agree with Burkeman when he says that this seems “absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short.”

We live most of our lives steadfastly according to the rule of the week. There’s our working week. Our four or five weeks of annual leave per calendar year. We measure projects, performance and progress in weeks. All the while, labouring under the delusion that we simply cannot run out of weeks.

“There’s always next week,” we keep telling ourselves.

While Burkeman’s book is a testament to living a truly fulfilling life by freeing ourselves of the impossible demands on our time and instead embracing our finitude on this remarkable planet Earth, I took another, somewhat unexpected lesson from this book – there’s a distinctive type of comfort we take from incrementally progressing through our lives, week by week, that keeps us from truly grappling with just how limited our time actually is.

In this sense, ‘weeks’ are effectively the inconspicuous collaborators in our slow but steady march towards our own inevitable demise.

This is particularly relevant in the context of complex, systemic and what can often seem to be intractable issues, such as climate change, that simultaneously take us outside the realm of our weekly lives and comfort zones.

Anyone who understands or trusts what climate scientists have been telling us for years knows the terrifying urgency of the climate crisis. They know the constant undertone of anxiety about what the future holds if we fail to rein in global emissions. They know the consistently difficult questions and choices that inevitably arise. How do I address this problem as an individual? Why do banks, pension funds and governments actively and willingly participate in the breakdown of our precious climate? What sort of a world are we creating for future generations? Should I reconsider having kids?

They know the solutions to the climate crisis are starting us in the face, but with every week that passes, hundreds of millions of tonnes of carbon emissions are produced globally. Every new or expanded fossil fuel project that is approved is another rusty nail in the coffin, another obstacle recklessly cast across our pathway towards a stable and habitable future.

As someone who has spent the better part of a decade campaigning for solutions to the climate crisis, I and many others alarmed about the stability of the Earth’s ecosystems exist in the chasm between a state of constant urgency to address problems much bigger than ourselves, and living by the unassailable weekly schedule of the world around us.

We need to see a major systemic shift where fossil fuel production and use begins declining rapidly and steeply as the uptake of clean energy capacity accelerates.

But systemic change often happens slowly and can’t be measured in weekly schedules or Google calendars. Until we reach a necessary tipping point that catalyses the acceleration of the global transition away from coal, oil and gas, we increasingly risk crossing one or several climate tipping points, many of which we are fast approaching.

With that in mind, I want to try and re-situate the climate crisis within a much broader scope than the highly-offensive 4,000 weeks we’re given on this planet, to provide an alternate perspective on just how little time we have on our hands to address it.

3,389,000 weeks. That’s about how long archaeological evidence tells us that humans have been living on this continent we now call Australia. If we measure this in terms of back-to-back, 80-year lifespans, it equates to more than 800 consecutive lifetimes.

13,700 weeks. That’s about how long ago the industrial revolution began. In that time, the ‘global economy’ has chewed through innumerable tonnes of coal, litres of oil and cubic feet of fossil gas.

2,856 weeks. That’s how long ago the Earth’s temperature has been rising at a rate of 1.7°C per century (note that this is less than our expected 4,000-week lifespan). Only 364 weeks later, in 1977, oil and gas major ExxonMobil had developed an understanding of the catastrophic impacts of human-induced climate change.

458 weeks. That’s how long ago 196 countries adopted the Paris Agreement, the primary goal of which is to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

12 weeks. That’s how long ago we found out that the monthly global surface temperature had been above 1.5°C for an entire year.

In a relatively short amount of weeks, we’ve managed to cause significant damage to some parts of our delicate biosphere. Unfortunately, our chances of causing irreversible and catastrophic damage are getting greater by the week.

From here on in, every week counts.

13 weeks. That’s how long governments around the world have to provide updated nationally-determined contributions (NDCs) to global emissions reduction efforts, as per the Paris Agreement.

222 weeks. That’s about how long we have until the global carbon budget for keeping warming to 1.5°C is exhausted. The coal, oil and gas expansion plans of just 190 companies would consume more than half of that budget.

274 weeks. That’s how long until 2030, the end of the so-called ‘critical decade’ for addressing climate change. Governments around the world currently plan on producing more than double the amount of fossil fuels during this time than would be consistent with keeping global warming to 1.5°C.

1,318 weeks. That’s how long until 2050, when the world has agreed to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

2,361 weeks. That’s how long Australia’s largest oil and gas company Woodside Energy wants to keep producing liquefied natural gas (LNG) at its North West Shelf project in Western Australia, pending approval from the Federal Government.

5,022 weeks. That’s about how long Australian coal miner Whitehaven Coal could be digging up coal at its Blackwater South mine, if approved.

The merciless truth is that we don’t have a lot of weeks left to navigate onto the right pathway to a stable climate future. We don’t have the weeks left for governments to continue approving new coal mines, or banks to keep financing companies undermining global climate goals, or superannuation funds to keep pretending their historically weak engagement efforts with undiversified fossil gas companies will reduce emissions.

A key challenge for any climate campaigner is attempting to reconcile the glacial pace at which systems change occurs with the urgency of the need for increasingly greater climate action. To understand and acknowledge that every action taken, every moment given to the cause, is important in and of itself, while living with the discomfort that ‘big wins’ or genuine progress tend to take time we don’t have.

But we will keep going. This week, next week, the week after that, and so on and so forth.

Other Finding Nature News

Listen!

You saw the video promotions for each September podcast. Amazing guests, amazing conversations. Weekly shows going deep with change makers and paradigm busters, going under the hood on what drives them, their philosophies and mechanisms to be the change.

Listen, subscribe, share and rate 🙏🏼

Attend!

We hit North Head Sanctuary and held Corporate Change Making in the Age of Greenhushing, Greenwashing & Greenwishing. Fantastic occasions!

This month we go to Barrington Tops for three days on Country at the invite of the Worimi People’s Traditional Elders.

Upcoming are more supper clubs, masterclasses, nature expeditions and Christmas Party. Head to Humanitix and hit follow to get immediate notifications on new events and ticket sales 🙏🏼

Support!

Finding Nature works with several organisations to deliver our content and experiences. If you’d like to learn more and expose your business or opportunity to our community, get in touch.

Altiorem is the world’s first sustainable finance library on a mission to change finance for good. Use the code FindingNature to get the first month off your membership.

Gilay Estate is a remarkable off-grid hut on the Liverpool Plains in NSW. Get to nature, get to Gilay Estate. Use the code Finding Nature at booking to receive a complimentary food bundle (free dinner & brekky) for every night you stay.